Spy fairy: The evolution of the tooth fairy in our home

Living Large is a monthly column about the strange (at least from the outside looking in) lifestyle of a modern, large family.

living large logo Living Large is a monthly column about the strange (at least from the outside looking in) lifestyle of a modern, large family.

Image: Matthew Naude

We don't teach our children about Father Christmas because we don't think that an overweight, elderly man who runs a North Pole sweatshop, enslaves elves and judges children is a good role model.

Now, if you do and are happy with Father Christmas's questionable morals, then there's no judgment from us, but when it comes to fantasy characters, Handsome Hubby and I don't put Father Christmas too high up on the nice list.

It's not because he is a fantasy character. I say this because some parents don’t introduce their children to any fantasy characters for varying reasons. One faction believes it’s not healthy psychologically. The thought is that fantasy stops children from being grounded in reality. I don’t know if there is any scientific truth to this, but I don't agree. I’ve seen with my children, especially when they are very young, that fantasy can help to deconstruct hard or traumatic concepts into meaningful bites.

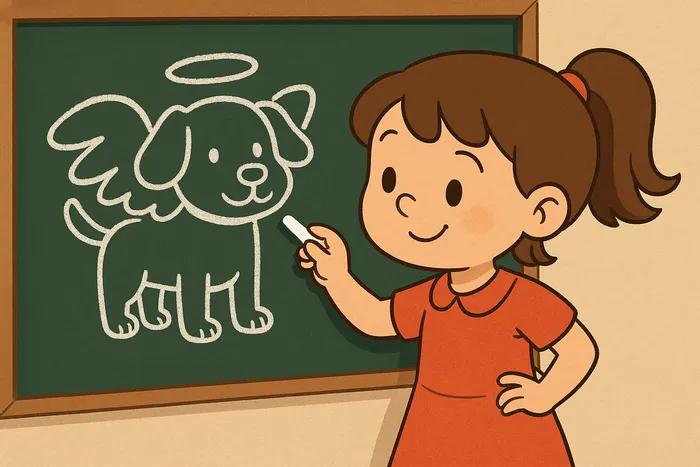

Like when my dad’s dog needed to be put down. Ruffy, a senior lady of 18 years, was in a lot of pain due to her advanced age. My children were devastated, no one more so than Jay, who could not understand why Ruffy had to be taken away.

Eventually, I told her that Ruffy was going to die, but she'd had a good, long life. I told her that when Ruffy got to heaven, God would give her angel wings so that she could fly.

This cheered Jay immensely, and she drew several pictures of angel Ruffy on the wall chalkboard for some time.

Jay was comforted by the idea that a beloved family pet would get angel wings in heaven after she was put down.

Image: chatgpt

Now, whether or not you believe in dogs, angels, or heaven, I don’t think dogs become angels when they die — but it comforted my daughter, so I had no qualms with the fantasy.

But, back to why some parents don’t like fantasy. Some people are cautious of fantasy for religious reasons. I am not among the throng that believes religion to be a fantasy in and of itself — as I’m sure you’ve guessed by now — but I do support the idea that fantasy and religion don’t always mix.

I don't think fantasy is good when it interferes with faith-based teaching, like Father Christmas.

Despite his name, Christmas is not actually about this guy at all. His character is, in fact, a bastardisation of Saint Nicholas, who actually happened to be a pretty stand-up guy and a much better role model to boot. The fantasy figure of Father Christmas doesn’t bring comfort or help with emotional transitions in any way, so we find him pretty pointless.

Case in point, when my youngest sister, who is 13 years my junior, was 7, she wrote a letter to Father Christmas asking for a PlayStation — among other things — and everyone forgot about it. Don’t judge us, she wrote it in June! When Christmas eventually came around, she was angry and disappointed to get gifts from everyone — nice gifts, mind you — but no PlayStation from Father Christmas.

Father Christmas teaches children to be good for a reward, which is otherwise known as bribery.

Now, a fantasy character that is helpful is the tooth fairy, or tooth mouse, depending on your preference. I have no religious attachment to my teeth, but losing a first tooth can be traumatic for a young child.

Eldest sobbed when she was five and lost a tooth after she bit into an apple. She was convinced it was her fault because she hadn’t brushed her teeth well enough.

Handsome Hubby found her crying. A few days before this, he had seen a documentary about girls entering puberty younger and younger, and this had traumatised him somewhat. Sadly, with this in mind, he tried to comfort her.

“Don’t worry,” he said. “This is normal. Your body is changing. You’ll see, eventually you’ll grow up and all your teeth will fall out.”

Eldest cried even louder.

“It’s not a bad thing. Your body must change. In a few years, you’ll grow breasts too.”

At this point, poor Eldest ran away screaming and came to find me in the other room where I was putting baby Jay down for a nap. I told Eldest that she didn’t need to worry because this was only a baby tooth, and a new tooth would replace it. I told her to put it in her shoe, and the tooth fairy would bring her money in exchange.

“How much money?” she immediately asked — her future, well-endowed, toothless self completely forgotten.

So, you see, the tooth fairy can be helpful, and while we are perfectly happy to keep the ruse going until my children are older, it can cause complications.

Like when we forgot to make the exchange a few times. We’ve had to come up with some innovative fibs when we forgot to swap out the money for the tooth:

“The tooth fairy is running late because she has too many deliveries.”

“The tooth fairy probably couldn’t find the shoe because your room is too messy.”

Jay, in particular, had me spinning more and more challenging yarns when she first learned of the tooth fairy. A very different personality from Eldest, she cared less about the money and more about this interesting figure of the tooth fairy. Not satisfied with a simple explanation, she wanted to know how the tooth fairy would know she had lost a tooth. How would the tooth fairy know which shoe to check? Where did the tooth fairy live? What did the tooth fairy do with the teeth?

The more answers I invented, the more the questions she had, and by the time she was satisfied, the tooth fairy I had made up had become a James Bond-meets-Ant-Man-like being, living in a fancy tooth palace in the clouds and using magical communication to run a modern spy operation which employed household pets and insects as informants.

The tooth fairy took on James Bond meets Ant-Man like proportions by the time five-year-old Jay was satisfied with the concept.

Image: chatgpt

As my children outgrew the fantasy, the older ones agreed by conspiracy to keep the fantasy going for the younger children.

School is also a factor in how long the fantasy is maintained. Sometimes schoolmates will destroy the fantasy or create it, as was the case with Father Christmas. While we didn’t teach our kids about Father Christmas, Rocky learned about him from friends in Grade R. Thankfully, by the time Christmas came around, we had weaned her off the fantasy.

A family acquaintance found that weaning his kids off the idea of Father Christmas happened naturally after he came to South Africa with his family. Italian by birth, he, his wife and four of his now nine children came to South Africa as missionaries. When Christmas came around, they found multi-cultural Father Christmases all over the place.

We South Africans aren’t picky about how our rainbow-nationed Father Christmases look — skinny, dark-skinned, fake beards clashing with black eyebrows, who cares. At one of our staff Christmas parties, we’ve even had a Muslim colleague don the costume. That’s right, we had a slamse Santa.

For one of our staff Christmas parties, a Muslim colleague had kindly donned the Santa costume.

Image: chatgpt

Anyway, back to the Italians. When the Italian kids, who were used to their anatomically correct Father Christmases of home, noticed that he looked completely different every time they turned a corner in South Africa, it became fairly obvious that he was fake.

• This is the last edition of Living Large on this platform, but not the last of the column overall. Talks are afoot for Living Large to find a new home. If you would like to keep reading, please reach out on my socials @authorlaurenoconnormay